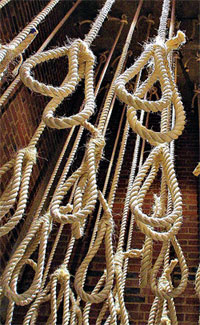

Humans crave justice, whether for 9/11 or apartheid’s horrors. Nooses make that point in a museum in South African.

Simon Wiesenthal, who survived Hitler’s death camps to become the most dogged of Nazi hunters, stressed that he was seeking “justice, not vengeance.”Either way, the feeling was sweet. A biographer, Tom Segev, wrote that the sight of former SS officers in shackles filled Wie senthal “with an elation akin to that evoked by divine worship.”

The revelers who celebrated the news earlier this month of Osama bin Laden’s death could relate. And few probably cared when the French publication L’Express countered that “to cry one’s joy in the streets of our cities is to ape the turbaned barbarians who danced the night of September 11.” But what is the appropriate response when evil meets justice? There may never be a definitive answer. In the meantime, there is no shortage of opinions.

As Maureen Dowd wrote in The Times, “those who celebrated on September 11 were applauding the slaughter of American innocents.” She called those who found joy in Bin Laden’s death “the opposite of bloodthirsty: they were happy that one of the most certifiably evil figures of our time was no more.”

They were also being human. The Times’s Benedict Carey cited research suggesting that such celebrations express a primordial, collective instinct.

Michael McCullough, a psychologist at the University of Miami, told Mr. Carey: “Revenge evolved as a deterrent, to impose a cost on people who threaten a community … In that sense it is a very natural response.” Still, some people aspire to be more like the Dalai Lama, who has urged compassion for Bin Laden, and to rise above our natural appetite for retribution.

“The antidote for revenge is not revenge,” said Izzeldin Abuelaish, a Palestinian gynecologist who lost three children in an Israeli attack. Dr. Abuelaish, the author of “I Shall Not Hate: A Gaza Doctor’s Journey on the Road to Peace and Human Dignity,” told The Times, “If I want to get revenge it will not return my daughters.”

Elie Wiesel, the Holocaust survivor and Nobel Peace Prize winner, told The Times that Dr. Abuelaish understood that “hate hates both the victim and the hater. One must not forget, but not use memory against other innocent people.”

Of course, there is a distinction between indiscriminate revenge against innocents and justice for murderers. Mr. Wiesenthal imagined that if he met victims of the Nazis in heaven, he would say to them, “I didn’t forget you.’’

Wiesenthal died in 2005 after helping to apprehend hundreds of war criminals . He did not live to see the latest and possibly last conviction of a Nazi. In 1993, an Israeli court found that John Demjanjuk was not the particularly cruel guard at Treblinka known as Ivan the Terrible, and he was freed. But on May 13, a German court ruled that Mr. Demjanjuk was guilty for his role as a guard at another death camp, Sobibor, and sentenced him, at age 91, to five years in prison.

Whether vengeance or justice, Mr. Demjanjuk’s victims did not appear concerned with his low rank.

“He is a very small fish,” Rudie S. Cortissos, whose mother died at Sobibor, told The Times. “But whether you are a whale or a sardine, someone who went wrong this way should be punished.”

KEVIN DELANEY

스마터리빙

more [ 건강]

[ 건강]이제 혈관 건강도 챙기자!

[현대해운]우리 눈에 보이지 않기 때문에 혈관 건강을 챙기는 것은 결코 쉽지 않은데요. 여러분은 혈관 건강을 유지하기 위해 어떤 노력을 하시나요?

[ 건강]

[ 건강]내 몸이 건강해지는 과일궁합

[ 라이프]

[ 라이프]벌레야 물럿거라! 천연 해충제 만들기

[ 건강]

[ 건강]혈압 낮추는데 좋은 식품

[현대해운]혈관 건강은 주로 노화가 진행되면서 지켜야 할 문제라고 인식되어 왔습니다. 최근 생활 패턴과 식생활의 변화로 혈관의 노화 진행이 빨라지고

사람·사람들

more

김응화 단장, 아쿠아리움 퍼시픽 ‘헤리티지 어워드’

김응화무용단의 김응화 단장이 롱비치의 아쿠아리움 오브 더 퍼시픽이 수여하는 2025년 ‘헤리티지 어워드’의 영예를 안았다. 올해 처음 개최된 …

이정임 무용원, 팬아시아 전통예술 경연대회

남가주 최대 규모의 아시아 전통 예술 경연대회인 팬아시아 댄스 앤 드럼 대회에서 이정임무용원의 청소년 단원들이 경연에 참가해서 전체 대상 등 …

유희자 국악무용연구소, 팬아시아 전통예술대회

지난 15일 샌개브리얼 셰라톤 호텔에서 열린 남가주 최대 규모의 전통 무용대회인 팬아시아 댄스 앤 드럼 대회에서 유희자 국악무용연구소(원장 유…

송년행사 안내해드립니다

다사다난했던 2025년이 이제 종착점을 향해 달려가고 있습니다. 한 해를 잘 마무리하고 2026년 새해를 힘차게 맞기 위한 다짐을 하는 송년 …

‘군중’ 시리즈 이상원 작가 첫 LA전시회

아케디아 소재 홈갤러리인 ‘알트프로젝트’(대표 김진형)가 오는 29일(토)부터 한국 블루칩 작가 이상원이 참여하는 전시 ‘인 드리프트(In D…

많이 본 기사

- 남가주에 또 폭풍우 최대 2인치 비 예보

- 공항 신원확인 강화… ‘리얼 ID’ 없으면 18달러 내야

- 1,600만불 메디케어 사기 일당 ‘… 2

- 매일 10분만 바꿔도… 당뇨 예방 6대 생활수칙

- [LA 오토쇼 특집] “자동차 시장 격동”… 전기·하이브리드 출시 ‘경쟁’

- 나란히 선 미 대통령·부통령 부인

- “최첨단 신차들 한 눈에”… 2025 LA 오토쇼 개막

- UC 등록금 치솟는다 “매년 최고 5% 인상”

- 아태계 대상 증오범죄 여전히 많다… 팬데믹 이전의 3배

- 체니 전 부통령 장례식… 부시·바이든 참석, 트럼프는 불참

- “행복하게 살았답니다”..신민아♥김우빈, 누적 기부액 51억 커플의 ‘해피엔딩’

- ‘트럼프 정적’ 코미 기소 “절차 위반”

- “웃음이 암을 낫게 한다”

- “히터도 못켜요”… 올 겨울 난방비 ‘역대급’

- [화제] ‘온통 황금’… 변기 하나에 1,200만불

- VA 34%·MD 30%만 모기지 ‘0’

- “미루면 더 아프다”… 40대 넘어서 뽑는 사랑니, 합병증 4.8배 급증

- VA·MD 등 6개주 주방용 냄비 리콜…납 오염 우려

- 업소탐방 - 대장금, 겨울 특선 콤보 출시

- 영어교재 ‘이것이 미국영어다’ 저자 조화유씨 별세

- “추수감사절 아침 가족과 함께 참여해요”

- 박시후, ‘유부남 불륜 주선’ 의혹에 입 열었다.. “휴대폰 절취 후 왜곡”

- “함께 만들어 가는 평화의 약속”

- “돈바스 넘기고 병력 감축”… 미·러 종전안 푸틴 입맛대로

- “OBBBA 법안으로 절세하세요”

- 김수현 측, ‘28억 소송’ 광고주에 “’미성년’ 故 김새론과 교제 NO”

- 워싱턴한인들, 하퍼스 페리 암벽등반

- 페어팩스 경찰, 3년간 불법 총기 110정 압수

- 연말시즌 온라인 샤핑 노린 사기 ‘기승’

- 재외국민까지 노리는 보이스피싱

- 이찬원, 2년 연속 ‘KBS 연예대상’ MC 발탁..이민정과 재회

- “해외서 한글로 쓰는 마음”… 재외동포문학상 시상식

- 트럼프, ‘DEI(다양성·형평성·포용성) 입틀막 협약’ 강요… 대학들 반발

- LA 교통정체 40년째 전국 ‘최악’

- 송지효, 父 ‘빚투’ 의혹.. “허위사실 유포, 형사고소” 강경 대응

- 트럼프 “조지아 단속 말렸다” “외국 전문인력 필요” 강조

- [조지 F. 윌 칼럼] 세계를 가장 크게 바꾼 사건, 미국 혁명전쟁

- 최소의 노력으로 최대 효과를 노리는 401(k)

- 첫 내집 마련 ‘꿈’ 40세로 늦어졌다

- 유엔 기후총회장서 화재 참석자들 긴급대피 소동

- 장기실업 수당 급증 197만건, 4년래 최대

- [LA 오토쇼 특집] “하이브리드 전성시대·안전기술 상향평준화”

- 100년 전 일본이 조선 수탈 위해 지은 은행을 보존한 이유

- 워싱턴 DC 주방위군 투입 트럼프 정책 법원서 제동

- “안전·깨끗한 한인타운 만들기” 함께 나선다

- 尹 “’제대로 했다’ 여론 있다”며 계엄 국무회의 CCTV 제출요청

- [한국춘추] 푸른 초원에 부국평화를 노래하며

- 연준, 다음달 기준금리 동결 전망 ‘우세’

- 2026년 은퇴플랜 대개편 총정리

- ICE, 뉴욕주법원서 이민단속 못한다

1/5지식톡

-

테슬라 자동차 시트커버 장착

0

테슬라 자동차 시트커버 장착

0테슬라 시트커버, 사놓고 아직 못 씌우셨죠?장착이 생각보다 쉽지 않습니다.20년 경력 전문가에게 맡기세요 — 깔끔하고 딱 맞게 장착해드립니다!장착비용:앞좌석: $40뒷좌석: $60앞·뒷좌석 …

-

식당용 부탄가스

0

식당용 부탄가스

0식당용 부탄가스 홀세일 합니다 로스앤젤레스 다운타운 픽업 가능 안녕 하세요?강아지 & 고양이 모든 애완동물 / 반려동물 식품 & 모든 애완동물/반려동물 관련 제품들 전문적으로 홀세일/취급하는 회사 입니다 100% …

-

ACSL 국제 컴퓨터 과학 대회, …

0

ACSL 국제 컴퓨터 과학 대회, …

0웹사이트 : www.eduspot.co.kr 카카오톡 상담하기 : https://pf.kakao.com/_BEQWxb블로그 : https://blog.naver.com/eduspotmain안녕하세요, 에듀스팟입니다…

-

바디프렌드 안마의자 창고 리퍼브 세…

0

바디프렌드 안마의자 창고 리퍼브 세…

0거의 새제품급 리퍼브 안마의자 대방출 한다고 합니다!8월 23일(토)…24일(일) 단 이틀!특가 판매가Famille: $500 ~ $1,000Falcon: $1,500 ~ $2,500픽업 & 배송직접 픽업 가능LA…

-

바디프렌드 안마의자 창고 리퍼브 세…

0

바디프렌드 안마의자 창고 리퍼브 세…

0거의 새제품급 리퍼브 안마의자 대방출 한다고 합니다!8월 23일(토)…24일(일) 단 이틀!특가 판매가Famille: $500 ~ $1,000Falcon: $1,500 ~ $2,500픽업 & 배송직접 픽업 가능LA…

케이타운 1번가

오피니언

조지 F·윌 워싱턴포스트 칼럼니스트

조지 F·윌 워싱턴포스트 칼럼니스트 [조지 F. 윌 칼럼] 세계를 가장 크게 바꾼 사건, 미국 혁명전쟁

이희숙 시인·수필가

이희숙 시인·수필가 [금요단상] 낙엽 위에 남겨진 향

김정곤 / 서울경제 논설위원

김정곤 / 서울경제 논설위원[만화경] ‘중동판 꽌시’ 와스타

[왈가 왈부] ‘패트 충돌’ 선고에 여야 “정치 판결” “자성 촉구” 아전인수?

수잔 최 한미가정상담소 이사장 가정법 전문 변호사

수잔 최 한미가정상담소 이사장 가정법 전문 변호사 [수잔 최 변호사의 LIFE &] 서울 가을 자락에서 만난 쉼터

강민수 을지대 첨단학부 교수 한국인공지능학회장

강민수 을지대 첨단학부 교수 한국인공지능학회장 [기고] 디지털 주권의 토대, 소버린 클라우드

1/3지사별 뉴스

ICE, 뉴욕주법원서 이민단속 못한다

뉴욕주법원이나 로컬법원 주변에서 빈번하게 이뤄지고 있는 연방 당국의 이민자 단속에 제동이 걸렸다.연방법원 뉴욕북부지원은 지난 17일 연방법무부…

트럼프, “외국인 전문인력 필요” 재차 강조

“함께 만들어 가는 평화의 약속”

“오늘 출범식은 단순한 시작이 아니라 한인사회와 함께 만들어가는 평화와 희망의 약속입니다. 한반도의 평화는 거대한 정치적 언어가 아닌 우리 같…

VA 34%·MD 30%만 모기지 ‘0’

오프라인 한국어 과정 성공적 마무리 단계

샌프란시스코 한국 교육원(허혜정 원장)이 2025년 가을 학기에 처음 개설한 오프라인 한국어 과정 ‘한국어 1’이 오는 22일 성공적인 마무리…

마라나타 비전교회, 장로/안수집사 임직및 장로 은퇴예배

오늘 하루 이 창 열지 않음 닫기

.png)

댓글 안에 당신의 성숙함도 담아 주세요.

'오늘의 한마디'는 기사에 대하여 자신의 생각을 말하고 남의 생각을 들으며 서로 다양한 의견을 나누는 공간입니다. 그러나 간혹 불건전한 내용을 올리시는 분들이 계셔서 건전한 인터넷문화 정착을 위해 아래와 같은 운영원칙을 적용합니다.

자체 모니터링을 통해 아래에 해당하는 내용이 포함된 댓글이 발견되면 예고없이 삭제 조치를 하겠습니다.

불건전한 댓글을 올리거나, 이름에 비속어 및 상대방의 불쾌감을 주는 단어를 사용, 유명인 또는 특정 일반인을 사칭하는 경우 이용에 대한 차단 제재를 받을 수 있습니다. 차단될 경우, 일주일간 댓글을 달수 없게 됩니다.

명예훼손, 개인정보 유출, 욕설 등 법률에 위반되는 댓글은 관계 법령에 의거 민형사상 처벌을 받을 수 있으니 이용에 주의를 부탁드립니다.

Close

x