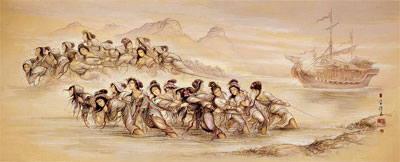

‘‘Female Boat-Haulers of the Sui Emperor Yang’’ is by Annie Wong, who supports equality for female artists . ART BEATUS

HONG KONG - Men dominated the Chinese contemporary art boom that began in the late 1980s and early ‘90s. While some women eked out artistic careers, none broke auction records or became quasi-celebrities. Even the era’s imagery - the military symbolism, Mao figures and giant leering faces - was macho.Two decades later, as new studies look back on that early underground scene, many are asking when China will be ready to produce a truly iconic female artist. The closest anyone came in the ‘90s was Xiao Lu, whose autobiography called “Dialogue,” after the name of her best-known work, was published in February through Hong Kong University Press.

In 1989, Ms. Xiao, a recent art school graduate, entered the National Art Gallery in Beijing - where an exhibition of avant-garde art had opened only hours earlier -took out a concealed firearm and shot two live bullets into her own entry in the show, an installation that involved phone booths. The incident earned her a brief jail stint and instant fame as a symbol of youthful defiance, particularly since it took place in the months leading up to the student demonstrations at Tiananmen Square. The work is now in a Chinese corporate collection, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York has a photographic print.

“Dialogue” could be called China’s first major feminist contemporary work of art. It shows a man and a woman talking to each other in phone booths; between them is a red phone with its receiver dangling off the hook. For years, Ms. Xiao, now 48, left the work unexplained. In her book she writes that it refers to a confrontation she had with an older family friend, a man who had assaulted her when she was a virgin, only to have him hang up on her.

Today, change is happening as more women become dealers, gallery owners, curators and experts.

“You could say that women artists have a different sensibility,” said Dr. Annie Wong, 80, the doyenne of the Hong Kong art scene and owner of Art Beatus, a leading Hong Kong gallery. “But the most important issue is the quality of the individual’s work. It’s about technique, education and effort, not whether someone is a man or a woman.”

For some, however, a nuanced perception was key. “Female artists are not different in the way they create works,” said Katie de Tilly, another Hong Kong gallery owner. “But they are different in the way they verbalize it.”

“They are better in tune with their personal experiences in life and able to communicate that as a whole,” she said.

Nicole Schoeni, owner of the Schoeni Art Gallery in Hong Kong, took over her family’s gallery when she was 23, after the death of her father, Manfred Schoeni, a veteran Chinese art dealer. She talks of a gradual change.

“When Dad started working in the 1990s, 95 percent of his represented artists were male,” she said. “It’s better now; but if you looked at a list of top names now, that list would still be male-dominated.

“But maybe young women were not encouraged earlier,” Ms. Schoeni, now 29, added. “And most museums and galleries at the time were run by men.” Gallery owners like herself also might be more willing to exhibit lesser-known female artists than their male counterparts.

Claire Hsu was 24 when she founded the Asia Art Archive in the Sheung Wan district of Hong Kong. Now 34, she runs the world’s largest collection of documentation on contemporary Asian art.

The AAA recently completed a major research project on the roots of contemporary Chinese art, in conjunction with the Museum of Modern Art in New York. “When we looked for artists to interview about the scene in the ‘80s, there were very few women,” Ms. Hsu said, and many of those around then have since given up their craft. “The most famous names are still not women.” Nor was she spared stereotyping by the China art world. “I’ve had quite a lot of correspondence sent to ‘Mr. Hsu,’ ” she laughed.

Still a working artist, Dr. Wong said she had no particular favorite piece, but pulled out a catalog of a show she had with Unesco on International Women’s Day in 2009.

“Female Boat-Haulers of the Sui Emperor Yang” (1996-97) is a 4.5-meter- long work based loosely on a painting by the Russian artist Ilya Yefimovich Repin of laborers pulling a barge.

Dr. Wong’s version is set amid a classic misty mountainscape. Two dozen women, yoked like cattle, strain to pull the imperial vessel of a historic tyrant. The figures are rendered like the gentle beauties of traditional Chinese art, only their pretty faces are distorted with pain and anger.

“It was really unequal before,” she said of women in the Chinese art scene. “People say our society is equal now ? but is it?”

By JOYCE HOR-CHUNG LAU

스마터리빙

more [ 건강]

[ 건강]이제 혈관 건강도 챙기자!

[현대해운]우리 눈에 보이지 않기 때문에 혈관 건강을 챙기는 것은 결코 쉽지 않은데요. 여러분은 혈관 건강을 유지하기 위해 어떤 노력을 하시나요?

[ 건강]

[ 건강]내 몸이 건강해지는 과일궁합

[ 라이프]

[ 라이프]벌레야 물럿거라! 천연 해충제 만들기

[ 건강]

[ 건강]혈압 낮추는데 좋은 식품

[현대해운]혈관 건강은 주로 노화가 진행되면서 지켜야 할 문제라고 인식되어 왔습니다. 최근 생활 패턴과 식생활의 변화로 혈관의 노화 진행이 빨라지고

사람·사람들

more

김응화 단장, 아쿠아리움 퍼시픽 ‘헤리티지 어워드’

김응화무용단의 김응화 단장이 롱비치의 아쿠아리움 오브 더 퍼시픽이 수여하는 2025년 ‘헤리티지 어워드’의 영예를 안았다. 올해 처음 개최된 …

이정임 무용원, 팬아시아 전통예술 경연대회

남가주 최대 규모의 아시아 전통 예술 경연대회인 팬아시아 댄스 앤 드럼 대회에서 이정임무용원의 청소년 단원들이 경연에 참가해서 전체 대상 등 …

유희자 국악무용연구소, 팬아시아 전통예술대회

지난 15일 샌개브리얼 셰라톤 호텔에서 열린 남가주 최대 규모의 전통 무용대회인 팬아시아 댄스 앤 드럼 대회에서 유희자 국악무용연구소(원장 유…

송년행사 안내해드립니다

다사다난했던 2025년이 이제 종착점을 향해 달려가고 있습니다. 한 해를 잘 마무리하고 2026년 새해를 힘차게 맞기 위한 다짐을 하는 송년 …

‘군중’ 시리즈 이상원 작가 첫 LA전시회

아케디아 소재 홈갤러리인 ‘알트프로젝트’(대표 김진형)가 오는 29일(토)부터 한국 블루칩 작가 이상원이 참여하는 전시 ‘인 드리프트(In D…

많이 본 기사

- 남가주에 또 폭풍우 최대 2인치 비 예보

- 공항 신원확인 강화… ‘리얼 ID’ 없으면 18달러 내야

- 1,600만불 메디케어 사기 일당 ‘… 2

- 매일 10분만 바꿔도… 당뇨 예방 6대 생활수칙

- [LA 오토쇼 특집] “자동차 시장 격동”… 전기·하이브리드 출시 ‘경쟁’

- 나란히 선 미 대통령·부통령 부인

- UC 등록금 치솟는다 “매년 최고 5% 인상”

- “최첨단 신차들 한 눈에”… 2025 LA 오토쇼 개막

- 아태계 대상 증오범죄 여전히 많다… 팬데믹 이전의 3배

- 체니 전 부통령 장례식… 부시·바이든 참석, 트럼프는 불참

- “행복하게 살았답니다”..신민아♥김우빈, 누적 기부액 51억 커플의 ‘해피엔딩’

- [화제] ‘온통 황금’… 변기 하나에 1,200만불

- “히터도 못켜요”… 올 겨울 난방비 ‘역대급’

- “미루면 더 아프다”… 40대 넘어서 뽑는 사랑니, 합병증 4.8배 급증

- ‘트럼프 정적’ 코미 기소 “절차 위반”

- “돈바스 넘기고 병력 감축”… 미·러 종전안 푸틴 입맛대로

- 김수현 측, ‘28억 소송’ 광고주에 “’미성년’ 故 김새론과 교제 NO”

- 추수감사 예배 통해 장애인 사랑 실천

- VA 34%·MD 30%만 모기지 ‘0’

- 연말시즌 온라인 샤핑 노린 사기 ‘기승’

- 영어교재 ‘이것이 미국영어다’ 저자 조화유씨 별세

- “웃음이 암을 낫게 한다”

- “해외서 한글로 쓰는 마음”… 재외동포문학상 시상식

- 첫 내집 마련 ‘꿈’ 40세로 늦어졌다

- 업소탐방 - 대장금, 겨울 특선 콤보 출시

- 박시후, ‘유부남 불륜 주선’ 의혹에 입 열었다.. “휴대폰 절취 후 왜곡”

- “추수감사절 아침 가족과 함께 참여해요”

- “OBBBA 법안으로 절세하세요”

- VA·MD 등 6개주 주방용 냄비 리콜…납 오염 우려

- 재외국민까지 노리는 보이스피싱

- [LA 오토쇼 특집] “하이브리드 전성시대·안전기술 상향평준화”

- 최소의 노력으로 최대 효과를 노리는 401(k)

- 트럼프 “조지아 단속 말렸다” “외국 전문인력 필요” 강조

- 유엔 기후총회장서 화재 참석자들 긴급대피 소동

- [조지 F. 윌 칼럼] 세계를 가장 크게 바꾼 사건, 미국 혁명전쟁

- 워싱턴한인들, 하퍼스 페리 암벽등반

- 2026년 은퇴플랜 대개편 총정리

- “함께 만들어 가는 평화의 약속”

- 송지효, 父 ‘빚투’ 의혹.. “허위사실 유포, 형사고소” 강경 대응

- “안전·깨끗한 한인타운 만들기” 함께 나선다

- 트럼프, ‘DEI(다양성·형평성·포용성) 입틀막 협약’ 강요… 대학들 반발

- 페어팩스 경찰, 3년간 불법 총기 110정 압수

- [한국춘추] 푸른 초원에 부국평화를 노래하며

- 이찬원, 2년 연속 ‘KBS 연예대상’ MC 발탁..이민정과 재회

- ‘포트2 확정’ 홍명보호 입장도 바뀌었다, 실현 바라야 하는 ‘이탈리아 루머’

- ICE, 뉴욕주법원서 이민단속 못한다

- 전기차 톱 8에 중국기업 5곳… “한국차 상품성 높여야”

- [삼호관광] 크리스마스 연휴에 떠나는 ‘유럽 스페셜 패키지’

- 워싱턴 DC 주방위군 투입 트럼프 정책 법원서 제동

- LA 교통정체 40년째 전국 ‘최악’

1/5지식톡

-

테슬라 자동차 시트커버 장착

0

테슬라 자동차 시트커버 장착

0테슬라 시트커버, 사놓고 아직 못 씌우셨죠?장착이 생각보다 쉽지 않습니다.20년 경력 전문가에게 맡기세요 — 깔끔하고 딱 맞게 장착해드립니다!장착비용:앞좌석: $40뒷좌석: $60앞·뒷좌석 …

-

식당용 부탄가스

0

식당용 부탄가스

0식당용 부탄가스 홀세일 합니다 로스앤젤레스 다운타운 픽업 가능 안녕 하세요?강아지 & 고양이 모든 애완동물 / 반려동물 식품 & 모든 애완동물/반려동물 관련 제품들 전문적으로 홀세일/취급하는 회사 입니다 100% …

-

ACSL 국제 컴퓨터 과학 대회, …

0

ACSL 국제 컴퓨터 과학 대회, …

0웹사이트 : www.eduspot.co.kr 카카오톡 상담하기 : https://pf.kakao.com/_BEQWxb블로그 : https://blog.naver.com/eduspotmain안녕하세요, 에듀스팟입니다…

-

바디프렌드 안마의자 창고 리퍼브 세…

0

바디프렌드 안마의자 창고 리퍼브 세…

0거의 새제품급 리퍼브 안마의자 대방출 한다고 합니다!8월 23일(토)…24일(일) 단 이틀!특가 판매가Famille: $500 ~ $1,000Falcon: $1,500 ~ $2,500픽업 & 배송직접 픽업 가능LA…

-

바디프렌드 안마의자 창고 리퍼브 세…

0

바디프렌드 안마의자 창고 리퍼브 세…

0거의 새제품급 리퍼브 안마의자 대방출 한다고 합니다!8월 23일(토)…24일(일) 단 이틀!특가 판매가Famille: $500 ~ $1,000Falcon: $1,500 ~ $2,500픽업 & 배송직접 픽업 가능LA…

케이타운 1번가

오피니언

조지 F·윌 워싱턴포스트 칼럼니스트

조지 F·윌 워싱턴포스트 칼럼니스트 [조지 F. 윌 칼럼] 세계를 가장 크게 바꾼 사건, 미국 혁명전쟁

이희숙 시인·수필가

이희숙 시인·수필가 [금요단상] 낙엽 위에 남겨진 향

김정곤 / 서울경제 논설위원

김정곤 / 서울경제 논설위원[만화경] ‘중동판 꽌시’ 와스타

[왈가 왈부] ‘패트 충돌’ 선고에 여야 “정치 판결” “자성 촉구” 아전인수?

수잔 최 한미가정상담소 이사장 가정법 전문 변호사

수잔 최 한미가정상담소 이사장 가정법 전문 변호사 [수잔 최 변호사의 LIFE &] 서울 가을 자락에서 만난 쉼터

강민수 을지대 첨단학부 교수 한국인공지능학회장

강민수 을지대 첨단학부 교수 한국인공지능학회장 [기고] 디지털 주권의 토대, 소버린 클라우드

1/3지사별 뉴스

ICE, 뉴욕주법원서 이민단속 못한다

뉴욕주법원이나 로컬법원 주변에서 빈번하게 이뤄지고 있는 연방 당국의 이민자 단속에 제동이 걸렸다.연방법원 뉴욕북부지원은 지난 17일 연방법무부…

트럼프, “외국인 전문인력 필요” 재차 강조

“함께 만들어 가는 평화의 약속”

“오늘 출범식은 단순한 시작이 아니라 한인사회와 함께 만들어가는 평화와 희망의 약속입니다. 한반도의 평화는 거대한 정치적 언어가 아닌 우리 같…

VA 34%·MD 30%만 모기지 ‘0’

오프라인 한국어 과정 성공적 마무리 단계

샌프란시스코 한국 교육원(허혜정 원장)이 2025년 가을 학기에 처음 개설한 오프라인 한국어 과정 ‘한국어 1’이 오는 22일 성공적인 마무리…

마라나타 비전교회, 장로/안수집사 임직및 장로 은퇴예배

오늘 하루 이 창 열지 않음 닫기

.png)

댓글 안에 당신의 성숙함도 담아 주세요.

'오늘의 한마디'는 기사에 대하여 자신의 생각을 말하고 남의 생각을 들으며 서로 다양한 의견을 나누는 공간입니다. 그러나 간혹 불건전한 내용을 올리시는 분들이 계셔서 건전한 인터넷문화 정착을 위해 아래와 같은 운영원칙을 적용합니다.

자체 모니터링을 통해 아래에 해당하는 내용이 포함된 댓글이 발견되면 예고없이 삭제 조치를 하겠습니다.

불건전한 댓글을 올리거나, 이름에 비속어 및 상대방의 불쾌감을 주는 단어를 사용, 유명인 또는 특정 일반인을 사칭하는 경우 이용에 대한 차단 제재를 받을 수 있습니다. 차단될 경우, 일주일간 댓글을 달수 없게 됩니다.

명예훼손, 개인정보 유출, 욕설 등 법률에 위반되는 댓글은 관계 법령에 의거 민형사상 처벌을 받을 수 있으니 이용에 주의를 부탁드립니다.

Close

x